Chase Less, Win More: How to Prioritize Your Time Pursuing Business

In the architecture, engineering and construction (AEC) industry, companies spend millions of dollars chasing projects that are never won. This costly and time-consuming process can leave some feeling as if the system is rigged against them.

Competitive bidding on projects may be in the client’s best interest. For some clients, that means one or two highly qualified design teams; for others the number might be as high as seven. It all depends on how well the owner has prequalified designers before a request for proposal (RFP) is sent.

There are usually differences between how the owner and the designer look at the project pursuit process. From the owner’s perspective, when multiple teams go after a project, it can spur innovative ideas, ensure a more competitive price and just generally give the owner more options for project partners.

Having multiple teams pursue work helps the owner understand the differences between competing bids and ultimately leads to more informed decision-making. If the owner is sophisticated and a repeat builder, for example, they’ll likely know what to look for. If the owner is less experienced, having multiple designers pursue the project provides the owner with a broad spectrum of options and insights for delivering a successful project.

Designers view the process differently. Competitive bidding can seem like an unnecessary step in the process, akin to a beauty pageant where appearance matters more than substance, or simply a way to get the ultimate project price down. From the designer’s point of view, too often the project pursuit process drains the designer’s time, energy and capital.

Ideally, a designer seeks a one-on-one relationship with the owner, helping the owner frame project needs and then winning the work because the designer demonstrated value in the process. The final step involves agreeing on contract terms and costs.

Chasing 10 projects to win two, three or five is challenging at best. Today there’s more than $1 trillion in construction work in the pipeline; using rough numbers, if the average capture rate (i.e., success rate chasing work) is 30%, that means the industry must chase $3.3 trillion of work to win every project in the pipeline. The cost of chasing work is significant, and both owners and designers must find a better way to collaborate to improve the project bidding/award process.

Market Forces are Impacting the Industry

The past several years have yielded a seller’s market, with many designers hitting record backlogs and achieving year-over-year revenue highs. A major driver behind this is the limited number of available designers relative to project demand — a dynamic that gives firms the upper hand to raise prices, improve margins and be more selective about the projects they pursue. In many segments, designers can cherry-pick opportunities and easily win new work. At the same time, a lack of team depth is a growing constraint, with some firms just one or two major projects away from stripping their bench of key project talent.

Clients don’t see things the same way. They want designers to bring the talent that will build the project as promised. The challenge? Even if a designer has said talent available at the time of bidding, they might not at the point when the owner reaches a decision.

Many designers find themselves using the same team on more than one project concurrently. It makes sense that a customer might want the strongest team available to work on their project, and some even specify people by name. The question becomes, can that designer charge a bit more for guaranteeing a particular team for a project? Can firms be fairly compensated for the higher risk of doubling or tripling the number of projects placed on their team? It’s supply and demand: When the supply of top talent is low and demand remains high, prices should go up.

The same can be said for innovative ideas that are brought forth during the project’s proposal and presentation stages. Naturally, the customer wants the best ideas for their project. For the designer, however, investing the time and talent to generate highly innovative ideas for one specific project can be costly.

There are only so many business development, conceptual design and estimating hours available for project pursuits. As a result, not all projects pursued get the degree of attention they deserve. Designers must make smarter, more strategic choices about the customers and projects they pursue.

The Real Impact of Capture Rates

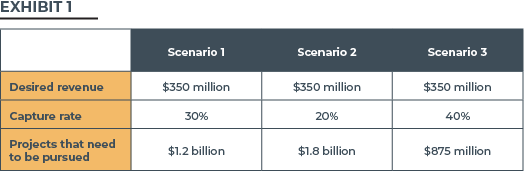

Designers are dramatically impacted by small changes in capture rates (i.e., the rate of project wins). Let’s look at some scenarios.

Exhibit 1 shows the impact of a company’s changing capture rates from 30% to 20% and 40%, respectively. If the company wants to end up with $350 million in work and at a 30% capture rate, it would need to pursue $1.2 billion in work actively. If the capture rate drops to 20%, that number goes from $1.2 billion to $1.8 billion, or almost a 50% increase in the number of projects the company needs to pursue.

Finding that much quality work to chase is daunting. Finding the time to conceptually design the project, bring in innovative ideas and prepare presentations is overwhelming, to say the least.

With the ever-present pressure to “chase more to win more,” it’s easy to get trapped on a hamster wheel, running faster and faster just to win sufficient work to keep the company profitable.

Now, if the capture rate for our example company rises to 40% (which is a high bar for most designers), then the company would only need to chase $875 million in work, or about 75% of what’s needed for a 30% capture rate.

Getting Off the Hamster Wheel

Winning profitable work starts long before a designer pursues a client or project. Here are some things designers can do to step off that tiresome hamster wheel:

- Get your strategy straight. It all starts with strategy. Which slices of the market do you want to target? Who are your right customers, what services do they need and how do these offerings set you apart from the competition? No one chases the complete commercial or institutional markets anymore; designers chase market slices. For example, you might want to target community colleges that are expanding their campuses to take advantage of students attracted to career and technical education over the traditional four-year college.

- Base your decisions on facts. Get smart about which market segments are growing, which are cooling off and which have already peaked. This isn’t to say you should only chase growing market segments, but it does alter the strategy for winning market share.

FMI uses a “4C model” to illustrate the context of profitable growth (see Exhibit 2). Start with the business climate you’re operating in (e.g., demographics, per capita income, government regulations, research and development, economic cycles), then dig into the changes, expectations and needs of customers. Since they’re the ones who will be buying your services, find out what criteria they use to select designers. Ask them about the competition (the third “C” in the model): find out what competitors are good at and how you can improve.

The last “C” in the model is your company and what you’re truly good at, simply average at and where you might lag behind the best designers in the market.

The 4 Cs come together to create the context behind crafting your go-to-market strategy. Simply put, that strategy identifies which market slice you’ll pursue, the right customers to target, your ideal projects (i.e., sweet spot) and your market differentiation.

3. Build a compelling story. You don’t have to be 100% differentiated from your competition; the key is identifying things you currently do (or could expand upon) that would create more value for your customers. If you simply match the competition already in the market slice, expect heavy price competition from entrenched designers. You need a story that explains to customers why YOU are the right choice for their project. Back up your story with proof that you can really deliver that additional value — and guess what? Customers will listen.

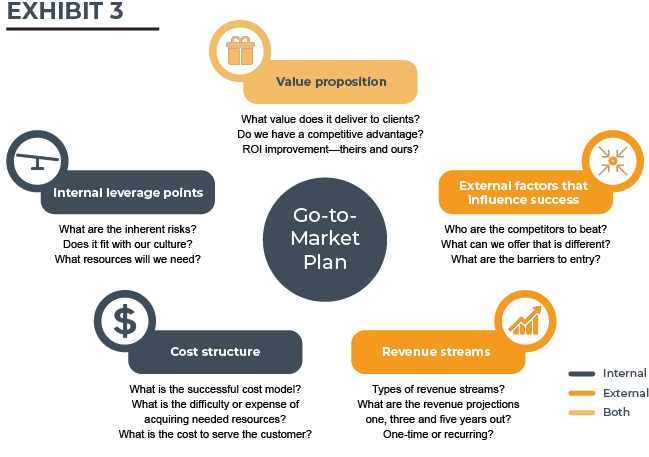

4. Build your go-to-market strategy. This strategy will help you define which customers to target and connect with before an RFP is issued — the point at which customers will be the most open to meeting and talking with you. You need to get in early and deep to build project-winning advantage. Exhibit 3 shows several key elements of a go-to-market strategy.

Remember, it’s in the customer’s best interest to have multiple designers chasing a project. But you don’t want to be just a number. Find ways to stand out and add value for your customers, then build your strategy around that value proposition.

5. Think like the customer. What about a given project is the same and what’s different from the customer’s other projects? What is the project’s business purpose? Who are the key end users that need to be included in the decision? What’s something the customer has struggled with getting other designers to hone in on?

Find out what the customer wants and why it’s important. What value do you bring that the competition lacks? Keep in mind that people spend more on things considered valuable. See if you can find something the customer values that your organization can deliver better than anyone else.

6. Put your time into your strategy. Build organizational capacity that’s centered on a key area of focus, such as spending time with customers in advance of submitting a bid. Remember that everyone is busy, so even when you do a good job targeting specific customers, many other things will be vying for your attention.

Why put millions of dollars toward trying to win bids and customers? Chasing work may be necessary for designers, but there are ways to make it less costly — and firms with solid bidding strategies are generally more successful and profitable than their hastier counterparts.

Getting smart about your go-to-market strategy, picking the right customers and pre-positioning yourself for the win will help you set up your company to gain profitable market share without breaking the bank.

.png)